In my last post I talked a bit about why I like learning languages while I discussed David J. Peterson' talk on the usefulness of languages. In this post, I’ll talk about minority languages, dialects, and heritage languages as I discuss Noah Higgs' talk.

Creating a new language course and dealing with heritage languages

Noah Higgs is a course builder for the Irish language at Duolingo. During his talk, he went through the process and the goals of adding such a language to Duolingo’s catalogue. Particularly, he told us about many delicate issues when creating a course for a minority language, and how the choices they make are impacted by culture, current setup of speakers, and notions of identity. For example, although many different people might be interested in learning Irish Gaelic, the intended audience for this course are people of Ireland who want to connect with this aspect of their culture, but might not necessarily feel entitled to it. For example, a dubliner with some contact with the Irish language but who did not have it spoken by their family at home. The responsibility of the course builder here is very big. They are trying to approach people who might not feel that the language could belong to them too.

One challenge of a speaker of a heritage language is the Kakapo problem. As I recently learned from a Kiwi friend, the kakapo (kākāpō, “night parrot” in Māori) is an endangered species of parrot from New Zealand. They are a very vulnerable species, developed in abundance of resources then suddenly exposed to predators. To mate, the males court the females by producing a sequence of loud low-frequency noises to call them from distance. Once the predators made the population decrease too much, the birds were too far away and they just couldn’t find each other anymore, making their numbers decline even further. Conservation programs created protected areas where they tackle extinction debt. Even though the predators or whatever external extinction catalysers are removed, the population can continue to decrease. Until the extinction debt is solved, in this case by trying to raise the population enough to get a certain critical mass, it can be very tough to get the population curve of an endangered species to go upwards again. I believe we can observe very similar phenomena with endangered languages such as Irish. I have not yet seen this term applied in this context, outside of biology, but since the terms “endangered” and “extinction” have already been applied to languages, I think it’s can be really useful to talk about extinction debt here too.

With languages, the process of increasing the number of speakers of an endangered or extinct ones is called, however, language revitalization. The availability of resources and support materials can play big role in that, so when a free platform like Duolingo offers a course in Irish, that is incredibly exciting.

As Noah explained, a heritage language can be defined as a language learned at home as a child but not fully developed due to insufficient input from the social environment. The reason can be because a family moved somewhere else where that language is not the main one spoken, or that a country was colonized by speakers of a language that has then become the official language of the country. In Ireland, some Irish is known by around 1/4 of the people, but it might be difficult to know who and where are those people. Like the Kakapos, when the Irish speakers can’t find each other, the opportunity for keeping Irish alive decreases. One problem for the learners here is that they likely share English as a common language. It might feel awkward to address someone new in Irish when you don’t know if both of you speak Irish, but you can guess that most likely both of you speak English. When you do know other speakers, it very easy to accidentally fallback to English when trying to practice, especially if you are an adult who is trying to become more proficient in Irish. This can make progress slow and can be demotivating. So besides promoting events where people can meet up especially to practice, on the Irish course on Duolingo they prioritise teaching communication sequences that help people continuing speaking Irish. For example, clarifying questions can be very useful for this (“What do you mean? Please, could you repeat that?").

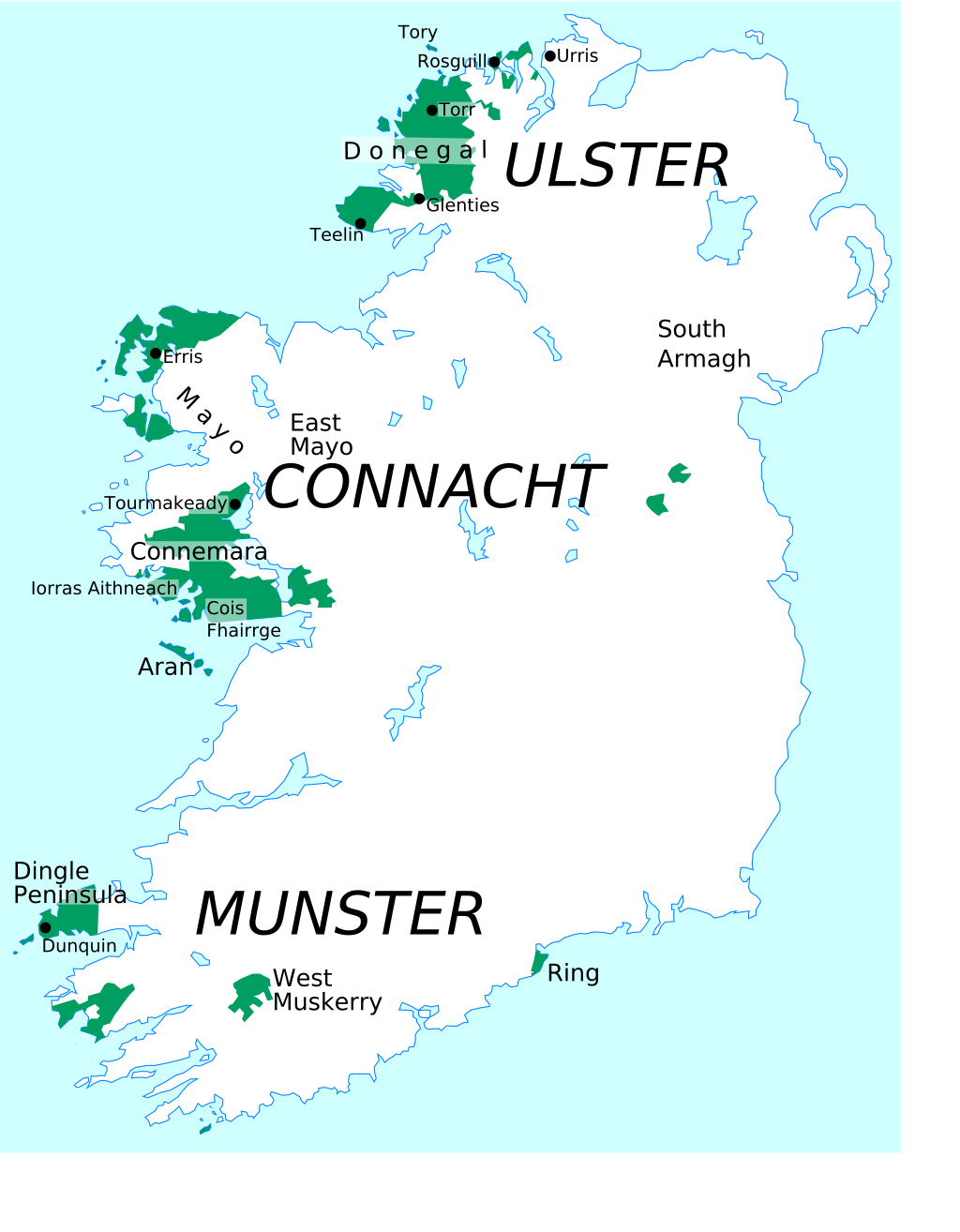

One other discussion that I found very interesting was the choice of which variant of the language is chosen to be represented in the course. Allowing multiple dialects can be confusing and not sticking to one can cause trouble. For example, my partner was studying Portuguese through another learning app and even though the course claimed to be Brazilian Portuguese, he was taught the word rapariga for “young woman”. However, that is the European Portuguese word for it. I raised a serious eyebrow when I heard him speaking that word out loud from the other room. Where I grew up, rapariga means prostitute. That caused us a good laugh, but you can see how potentially dangerous these variations could be. When you’re trying to raise the status of a minority language that has several dialects within, all facing distress, it also deals very strongly with the emotional aspect of representation. In the case of Irish, they opted to teach the most common variant. Unfortunately, that means people who want to see smaller dialects being represented could feel left out.

Basing this choice on the dialect with most number of speakers does not always have to be the case, as intricate political aspects and other factors might also apply. For example, Arabic is often considered one of the hardest languages to learn, the dialects of Arabic are very different, and there are many countries where it is spoken. Picking the variant of a specific country when creating the Arabic course is delicate and might mean restricting your interactions to only a subset of the Arabic speaking world. So in that particular case, they opted for a more international version called “Modern Standard Arabic” that has the goal of being understandable more widely. The con side here is that maybe it doesn’t sound very natural, but so far the feedback I’ve seen from native Arabic speakers in the Duolingo community has been great.

As usual, nuance and goals make a difference in this choice, but this challenge will be present for most languages. My partner’s mother tongue is a very specific dialect of German, Südtirolerisch, a variant of Southern Bavarian spoken in the region of South Tyrol, Italy. Before I met him, I didn’t even know that there were places in Italy where German was spoken. Now I want to learn his mother tongue, especially as many members of his family don’t speak English.

My approach to this so far was trying to learn Standard German first, which I had already learned a bit before I met him, then deal with the differences between that and his dialect later. But I am becoming increasingly skeptical of this approach. The reason is that I got to a certain level of German where I can now follow series and watch it together with him, but I still can’t understand him unless he makes an effort to speak standard German and even then it is still too difficult to not just give up and use English, the language we always communicated at. It is still very hard to find resources for learning a dialect sometimes but I decided recently to change my approach and I’ll report on it once I’ve tried it for a while. Are any of you trying to learn a language or dialect not spoken by a lot of people? Does it have variants or similar languages more widely spoken? What methods are you using for learning?

You can watch the whole stream of DuoCon, including Noah’s talk, here.